Do my Bacteria Get Cold?

This post first appeared on Cold Weather Aquaponics. Keeping up our trek through the list of aquaponics winterization techniques (in no particular order), this week we turn to water chemistry. This post will provide an explanation for why nitrification in cold water offers us a challenge. It assumes you've digested the basics of nitrification. If you haven't, read up here. The next technical post will give you a guide for sizing your biofilter. As you read this, keep in mind that I'm not a chemist, a biologist, or a bio-chemist, and this is not my area of expertise. I'd recommend taking this post with about 500 ppm of salt. I'm only going into this issue because it's essential for cold weather operation.

Keeping up our trek through the list of aquaponics winterization techniques (in no particular order), this week we turn to water chemistry. This post will provide an explanation for why nitrification in cold water offers us a challenge. It assumes you've digested the basics of nitrification. If you haven't, read up here. The next technical post will give you a guide for sizing your biofilter. As you read this, keep in mind that I'm not a chemist, a biologist, or a bio-chemist, and this is not my area of expertise. I'd recommend taking this post with about 500 ppm of salt. I'm only going into this issue because it's essential for cold weather operation.

- Passive Solar Greenhouse Design

- Insulated and Air-Sealed Fish Tanks and Grow Beds

Insulated Piping- Multiple Layers of Thermal Protection for Plants

- Fish Selection for Cold Hardiness

- Plant Selection for Cold Hardiness and Freeze/Thaw Tolerance

- Efficient Water (Not Air) Heating

- Programmable Temperature-Dependent Pumping Controls

- Strategies for Maximizing Nitrification in Cold Water

- Aquaponics-Integrated Hot Tubs (Seriously)

Cold Water Nitrification

In some ways this post puts the cart before the horse because we haven't gotten into seasonal water temperatures and the reasons for them. For the meantime, I hope you'll just trust me that keeping warm water in a backyard aquaponics greenhouse in a climate like mine is foolish. Lots of people do it. But then again, lots of people buy huge off-road vehicles and never go off road. Go figure.

Anyhow, assuming that you'll be lowering your water temperatures down to 50°F or lower in winter, you'll need to start thinking about bacteria.

Anyhow, assuming that you'll be lowering your water temperatures down to 50°F or lower in winter, you'll need to start thinking about bacteria.

If you're not familiar with the bacteria that live in your aquaponics system, welcome to the club! Some may try and pretend that we understand the bacteria in our systems, but in reality it's 99.9% mystery. We know that some things work, and that's what we do. But in truth, humans know more about the farthest reaches of space than we do about our own soil bacteria. For more on this, read Teaming with Microbes: A Gardener's Guid to the Soil Food Web. But I digress.

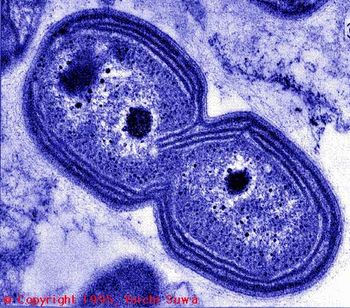

For the purposes of nitrification (converting ammonia to nitrite then to nitrate), there are two types that do the work. Or, rather, we group bacteria into these two types depending on the work that they do. Nitrosomonas bacteria convert ammonia (toxic to fish) to nitrites (even more toxic to fish). Once that step is done, Nitrobacter then convert nitrites to nitrates (not very toxic to fish).

By the way, "convert" as it's used here is a euphemism for "eat the one thing and poop out the other," in the same way that we "convert" Cracklin' Oat Bran into little rocks. There are two things that get otherwise squeamish people comfortable talking about poop. One is gardening. The other is raising children.

This beautiful, magical process works wonderfully and (usually) reliably in our aquaponics systems. Mine has gotten so reliable that I only check my ammonia and nitrate levels once a month (or whenever the neighbor kids want something to do).

However, like most things, this slows down when it gets cold. I can relate to this. When it's 10°F outside, it takes a lot to get me off the couch and out the door for a run. I have to put on a jacket, a hat, gloves, maybe a mask, and the whole darned thing is uncomfortable. Bacteria is the same way. Converting ammonia is such a bother. I need a nap.

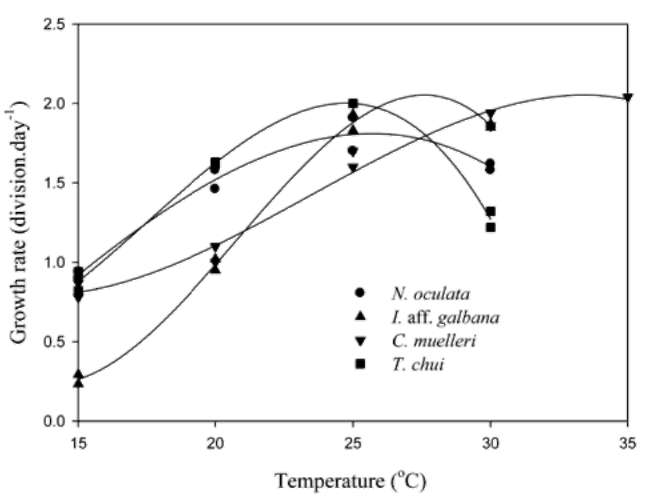

Fortunately, this cold-weather slowdown is predictable, as the following charts show us. I've copied a bunch of them because the results don't all agree with one-another and I don't have a clear way of determining which is most accurate.

Nitrification Rates by Temperature in Soil

http://www.ipm.iastate.edu/ipm/icm/2001/10-22-2001/why50.html[/caption] [caption id="" align="alignnone"

Various Nitrifying Bacteria Growth vs. Temperature in Aquaculture http://ejournal.sinica.edu.tw/bbas/content/2012/1/Bot531-12/Bot531-...

Nitrification Rates by Temperature in Aquariums

http://www.prirodni-akvarium.cz/en/index.php?id=en_cycling

According to the US EPA, most strains of nitrifiers grow optimally at temperatures between 77 and 86°F, but nitrification has occurred over a wide range of temperatures (46-79°F).

This article suggests that nitrifying bacteria can operate at even lower temperatures than the studies listed above.

What this all means for you is that the rules of thumb for biofilter and/or grow bed sizing proposed by most of the sites and books about aquaponics may not serve you well when your water temperatures dip below about 50°F. Stay tuned for the next technical post on how to size your biofilter.

What do you think - have you had issues with cold weather nitrification?

Comment

-

Comment by Vlad Jovanovic on September 26, 2014 at 10:29am

-

Yes, most any inorganic carbon species food source (like sugar) would likely do. Only you need to be careful, and use a known amount of C. The use of 80 proof Vodka and the subsequent amounts and methods needed have been somewhat "well documented" in the Land of Aquaria (pun intended). Sugar, has not (at least not to my knowledge...which doesn't mean that it hasn't, just that I am not aware of such documentation)...

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 26, 2014 at 10:21am

-

Thanks! Can I ask what you mean by "carbon species?"

I'd assume sugar would perform the same function as vodka, right? I can think of better uses for Vodka :)

-

Comment by Vlad Jovanovic on September 26, 2014 at 10:17am

-

Right-O...then it makes sense. Your not after a "self-contained" low fish density efficient plant growing system.

Yes, solids removal and nitrate management will be very important then. And since you have land and a garden, we can then look at your entire property (operation) as "your system" and NOT just the AP portion...AP solids providing a needed input for your soil based endevours...

You can also "denitrify" the AP system by introducing an extra carbon species food source (like Vodka) and then skimming off the excess bacteria that have sequestered the NO3...dump them on your trees/garden/compost pile...whatever...where they may do more good for, than if you were to put the N back into the air as N2...

Just an thought

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 26, 2014 at 10:08am

-

Per the last question, I would use the removed solids in my regular garden or with seedling starts.

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 26, 2014 at 10:06am

-

You've got it. My primary interest is in fish.

I grow for my family. Currently I raise 100 tilapia in summer, 50 trout in winter, which still doesn't produce as much fish as I'd like. However, I get more lettuce, spinach, and herbs than we could possibly eat. The rest of my veggies I grow in soil. I don't want to sell my produce, so increasing fish production is my goal.

As you could guess, this produces an excess of nitrate, which I currently manage through occasional water changes, though I'm experimenting with bird netting and anaerobic denitrification. Partial solids removal would help a lot too.

-

Comment by Vlad Jovanovic on September 26, 2014 at 9:58am

-

I take it that your true AP interests lie mostly in the fish aspect then?

You are aware of the tremendous amount of plant essential elements within those solids you are trying so hard to remove, right?

How do you re-process those and introduce them back into the system?

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 26, 2014 at 9:46am

-

Thanks Vlad!

So.. presuming I did filter out all (or nearly all) solids I could significantly reduce media bed sizing. This seems like a good deal as media is either very expensive or very heavy. While solids filters are somewhat more complex to build, they're not that hard.

So... if I did that, I'm still left with the fact that my media beds will have less DO than a moving bed biofilter will have. I've looked at the math around hydraulic loading and BOD5 estimation, and I don't have the time or wherewithal to truly get my head around it.

That makes me want to find a derating factor for media beds vs. biofilters. I can derate for the percentage of time that they're not flooded. That's easy. Accounting for oxygen I'm not sure how to do yet.

By the way, the GB size for 13 lbs of fish was for a 1x1, not 1x3. That makes it even more extreme.

At the end of the day, I'd love to be able to tell people that they could use 6" deep beds for non-tap-rooted crops if they had a solids filter.

-

Comment by Vlad Jovanovic on September 26, 2014 at 9:33am

-

You probably could...IF you removed all solids and fines and were relying on that 1x3 bed with 1/2" gravel TO ONLY PERFORM BIO-FILTRATION (read: ammonia oxidation) DUTIES

Those numbers you posted are based on the particular medias SSA (Specific Surface Area). That SSA then determines the systems BSA (Biological Surface Area).

In Aquaponics however, when choosing a media and developing system ratios, SSA is just ONE parameter you need to take into account (percolation, particle size etc... are some of the others). This is because your media bed is much more than just a bio-filter in AP. AP 'Rules of Thumb' and published system ratios have as much to do with (if not more actually) with mechanical filtration, as they do bio-filtration.

Hope this helps to resolve (at least in part) your mental quandary on the matter

...

...

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 26, 2014 at 7:10am

-

Hey Guys,

I've been working on the 2nd post but having a tough time. The best information I can find on biofiltration capacity is from aquaculture. However, the amount of media you need in a moving bed biofilter is presumably smaller than the amount you'd need in a media bed. Here are some numbers I worked out:

Media Lb Feed Lb Fish 1 mm Sand 2.49 165.98 Gravel 1/4" 0.39 26.14 Gravel 1/2" 0.20 13.07 Gravel 3/4" 0.13 8.71 MB3 0.37 24.53 Kaldnes 0.49 32.53 Bioballs 0.32 21.33 I realize the sand and small gravel estimates are innacurate because solids will cover much of the surface area. I also suspect that these media would not provide as much filtration in a grow bed as in a dedicated biofilter due to insufficient oxygen, but I can't figure out how to quantify that.

As it looks up there, I could raise 13 lbs of fish on a 1 ft3 grow bed of 1/2" gravel. That flies in the face of everything I've read up till now.

Any ideas?

-

Comment by Jeremiah Robinson on September 22, 2014 at 7:57am

-

Wow, thanks Rob. Consider my mind blown. A brief lit. review reveals...

Archea are not bacteria, and can operate in many extreme environments.

They can skip the ammonia portion of the nutrient cycle entirely, and convert urea directly to nitrite.

As with most microbial life, we know jack about how they operate.

Scientists are just now learning how to detect their presence.

© 2026 Created by Sylvia Bernstein.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Aquaponic Gardening to add comments!

Join Aquaponic Gardening